What are Signals?

Let's start with an extremely broad definition:

A signal is a value that changes over time and whose change events can trigger side effects.

A signals library, or framework, provides a cohesive set of tools for managing these changing values and their side effects in an automated way that ensures consistency. This allows developers to spend less time thinking about how updates are propagated through a system and more time focusing on what those updates should be. It also prevents whole classes of easy-to-introduce-but-hard-to-find bugs that can occur due to accidental mismanagement of derived state or side effects.

There are many well-known software patterns matching this description, but that we wouldn't normally call 'signals'. For example, using the above definition you could argue that React is a signals library specifically for UI view trees.

This might seem like a trivial comparison to draw, but it's a useful one to explore because signals are pure uncut reactive values, and frameworks like React incorporate the same fundamental concepts into more involved APIs.

To illustrate, let's break signals down to understand their component parts.

Breaking signals down

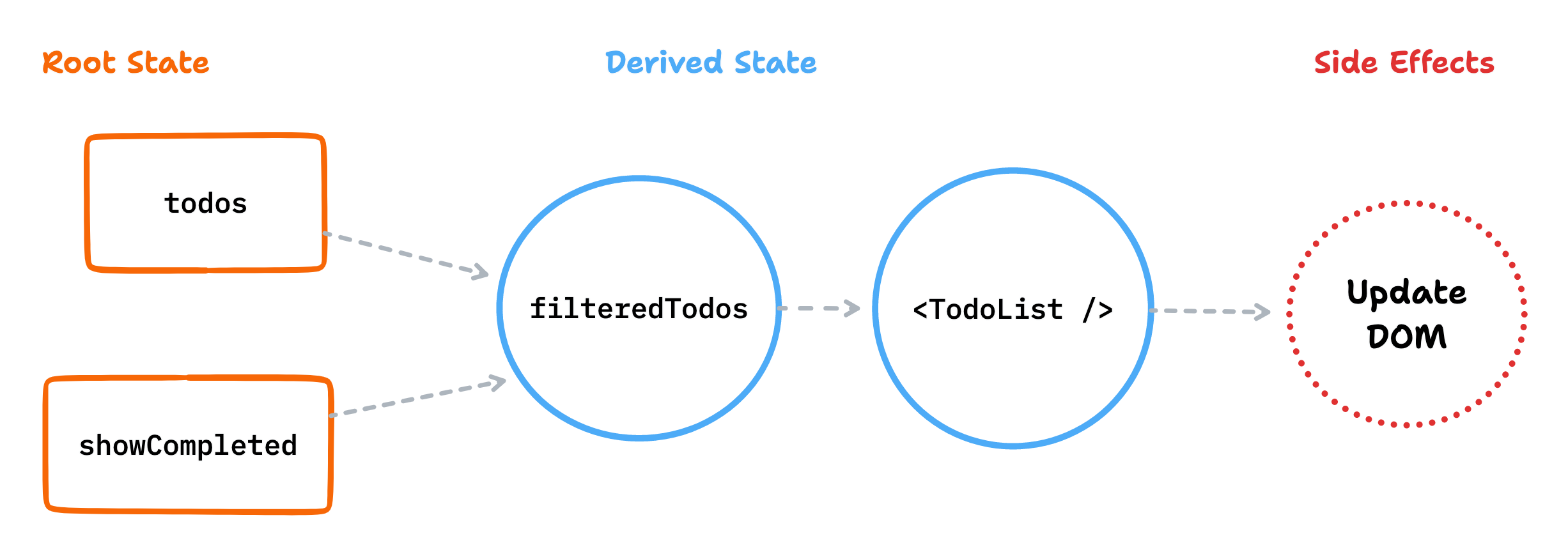

Signals libraries or frameworks are typically based on three primitives:

Root values

A root value is any state value that is updated directly, normally in response to external events, e.g. user input.

infoIn a modern idiomatic React app,

useStateoruseReducerare for managing root values.A common good practice is to make sure you don't store the same piece of information in multiple root values, so that each 'fact' in your system has a single source of truth. Otherwise, you risk getting into a situation where the values are out of sync.

Derived values

A derived value is any state value that is computed exclusively by looking at other state values.

infoIn a React component, the rendered tree is a derived value. Any intermediate data you compute during a component's render function is also derived, e.g. a filtered list of todo items in a todo app.

A key component of signals is that derived values are automatically recomputed when their dependencies change. This is a huge win over manually managing derived values, which is error-prone and can lead to subtle hard-to-find bugs.

Side effects

A side effect is any process which runs in response to a state change event.

infoIn React, updating the DOM is a side effect which is managed by React itself. It also provides

useEffectfor executing custom side effects in response to changing values.

Let's look at a simple Todo list React app to see how these primitives map to code.

function TodoApp() {

const [todos, setTodos] = useState<Todo[]>([{ text: 'buy milk', completed: false }])

const [showCompleted, setShowCompleted] = useState(false)

const filteredTodos = useMemo(() => {

return todos.filter((todo) => !todo.completed || showCompleted)

}, [todos, showCompleted])

return (

<>

{/* ... */}

<TodoList todos={filteredTodos} />

</>

)

}

The Signals Design Space

On top of this foundation there exists a wide spectrum of features and design decisions that each signals implementation may approach differently. Here's just a few:

How do you access the value of a signal?

- Are the signals explicitly wrapped?

- Does a compiler do the unwrapping on your behalf?

- If not, is it

get(wrapper)orwrapper.valueorwrapper.get()orwrapper()?

In idiomatic React code this is complicated. Values are unwrapped and can be tricky to read depending on where they are defined, e.g. folks frequently accidentally read stale values.

How does data flow?

There are two main approaches to propagating root state changes: push and pull.

Generally speaking pull is simpler to work with because derived values are computed on-demand, i.e. lazily. This can avoid unnecessary recomputation of derived values. However, in some situations push can be more performant because it has lower overhead.

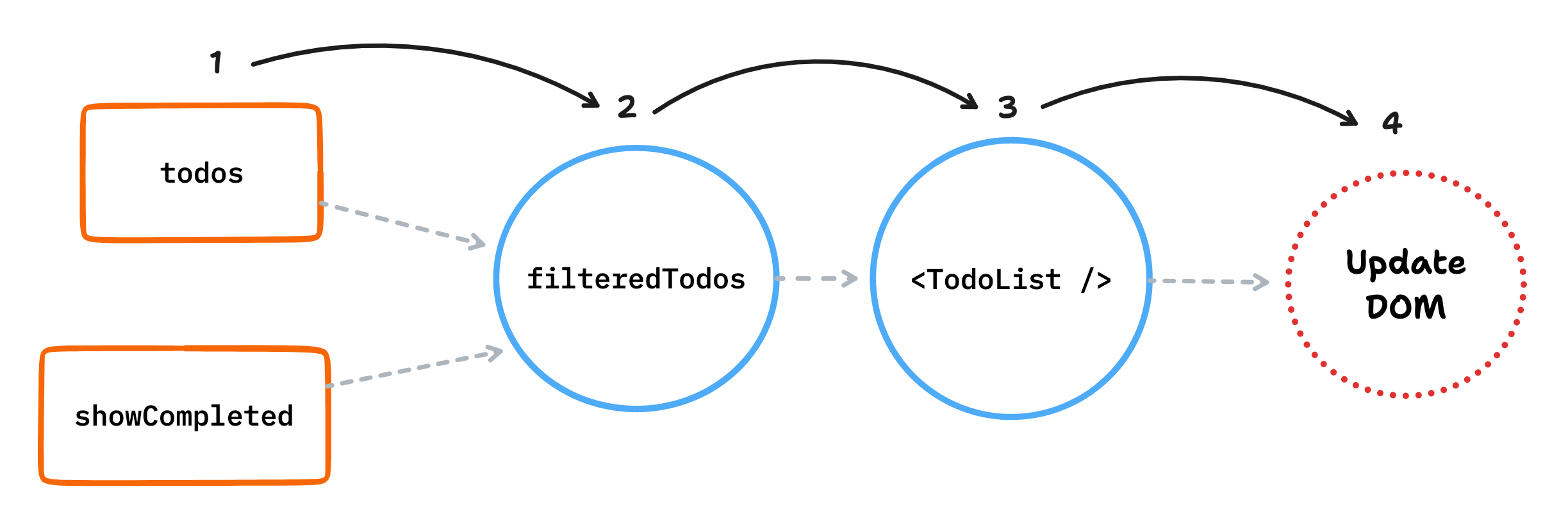

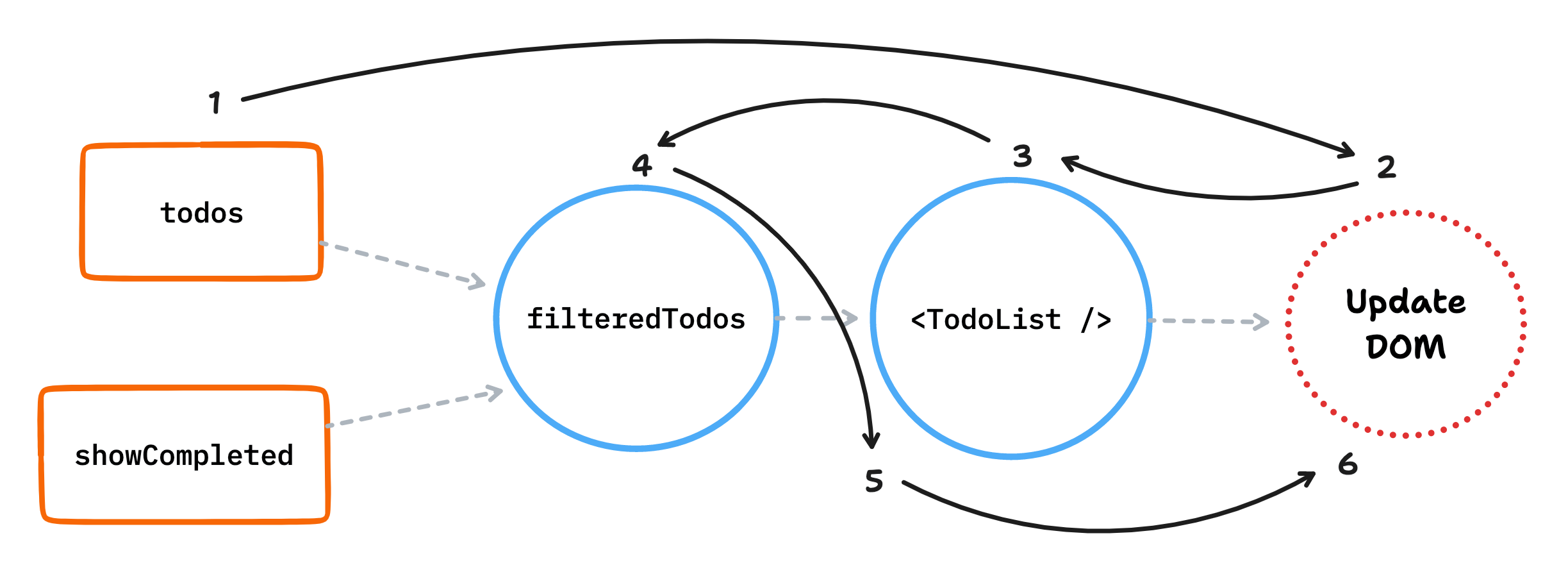

Push

When you change a root value, any derived values that read from it are immediately updated, and so on, from left to right.

- The

todosvalue is updated. - The

filteredTodosvalue is updated. - The

<TodoList />value is updated. - The side effect is triggered.

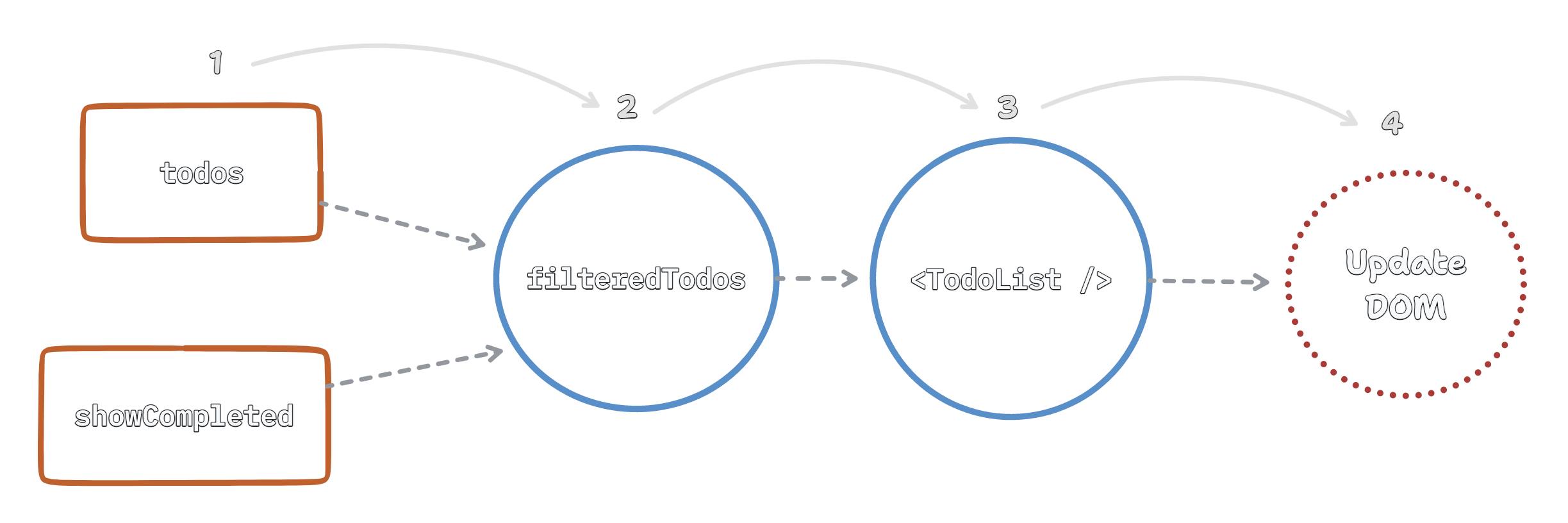

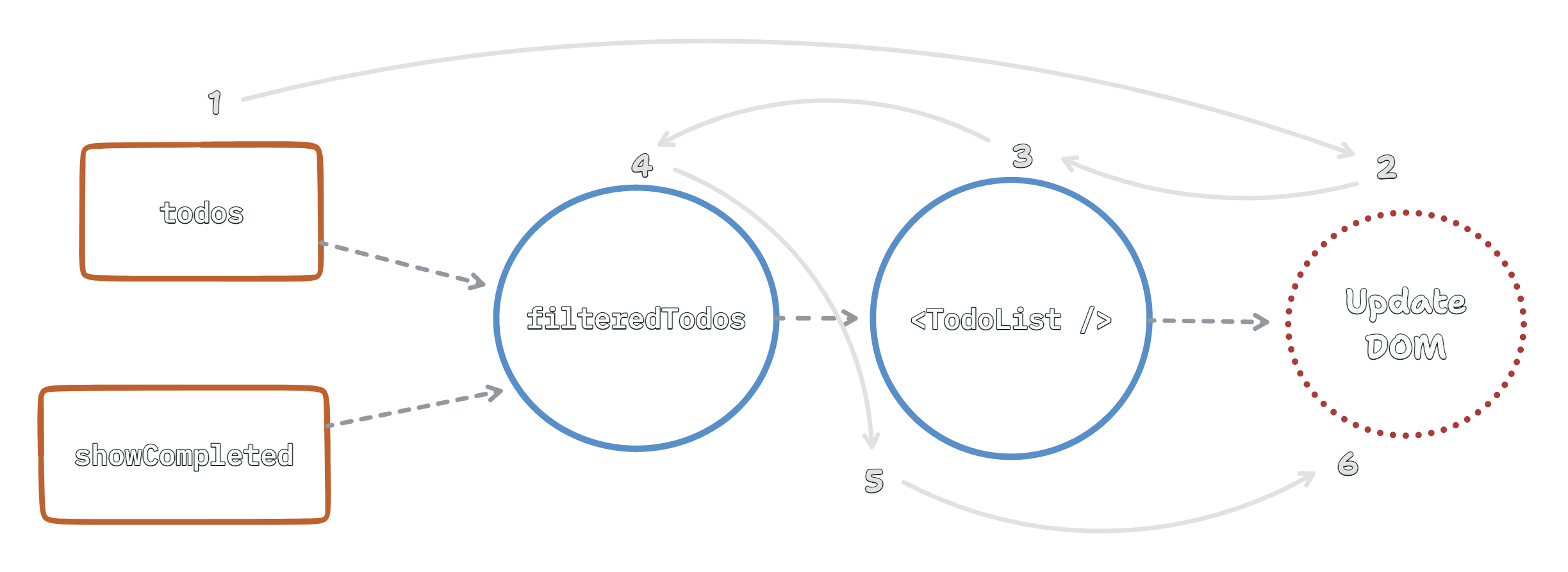

Pull

When you change a root value, any side effects that might need to execute are notified. Upstream derived values are only recomputed if they are read from.

- The

todosvalue is updated. - The side effect is 'maybe' triggered, and reads the

<TodoList>value to see if it changed - The

<TodoList>value is 'maybe' recomputed, and reads thefilteredTodosvalue to see if it changed - The

filteredTodosvalue is recomputed because it's root dependency changed - The

<TodoList>value is recomputed because thefilteredTodosvalue changed - The side effect is triggered

React is a mixture of push and pull. Derived values are updated in 'push' mode during a render, but renders are evaluated in a larger 'pull' context.

How are derived values created and cached?

Since derived values are computed by looking at other state values, there must be some way of knowing which other state values are used so that the derived values can be recomputed automatically.

Some signals implementation use explicit dependency declaration. Indeed, React's useMemo is a way of managing derived values with explicit dependency declaration.

const fullName = useMemo(() => {

return `${firstName} ${lastName}`

}, [firstName, lastName])

Other signals implementations use automatic dependency capturing, either supported by a compiler or, more commonly, by using wrapped values. This is a less-restrictive approach because it means you don't need direct access to the dependency values, and you don't need to worry about keeping the dependency list up to date.

This is how the same thing would look using signia

const fullName = computed('fullName', () => {

return `${firstName.value} ${lastName.value}`

})

In both cases, the results of the computation are cached so that they are only recomputed when one of the dependencies changes.

Other variables

- What kinds of side effects can be triggered?

- Only UI updates, or any old side effect?

- Are the signals standalone, bolted on to a framework, or integrated into a framework from the ground up?

- Can the signal dependency graphs form a tree, a directed acyclic graph, or a directed cyclic graph?

- Do they support bi-directionality (e.g. lenses)?

- Do the signals support 'batching', i.e. transactions?

- If so, can changes be rolled back when a transaction aborts?

Okay but what do people actually mean by the term 'signals'?

The term 'signals' is typically, but not always, talking about reactive values with:

- explicit wrappers

- automatic dependency capturing

- directed acyclic graphs

- bolted on to a framework

Here are some examples of libraries or frameworks that implement signals:

Conclusion

- Signals are just a way to model and use reactive data, and they do it in a very pure, stripped-down way.

- There are a million implementation details that give flavor to a particular signals library. Some big differences, some small differences, but the core concepts are shared.